Sensitivity Analysis

Lecture 19

November 24, 2025

Review and Questions

Mathematical Programming and Systems Analysis

Pros:

- Can guarantee analytic solutions (or close)

- Often computationally scalable (especially for LPs)

- Transparent

Cons:

- Often quite stylized

- Limited ability to treat uncertainty

Mathematical Programming and Systems Analysis

Challenges include:

- Complex and non-linear systems dynamics;

- Uncertainties;

- Multiple objectives.

Multiple Objectives

- A priori vs a posteriori treatment.

- We say that a decision \(\mathbf{x}\) is dominated if there exists another solution \(\mathbf{y}\) such that for every objective metric \(Z_i(\cdot)\), \[Z_i(\mathbf{x}) > Z_i(\mathbf{y}).\]

- \(\mathbf{x}\) is non-dominated if it is not dominated by any \(\mathbf{y} \neq \mathbf{x}\).

- Pareto front: set of non-dominated solutions, each of which involves a tradeoff relative to the others.

Uncertainty and Optimization

Conceptual Assumptions of Optimization

Most optimization frameworks implicitly assume perfect specifications of:

- Model structures/Parameter values

- Decision alternatives

- Probabilities/distributions

A Relevant “Quote”

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.

– Often attributed to Mark Twain (apocryphal)

How Do We Deal With Misspecification?

If we know something about probabilities: Monte Carlo or decision trees…

What if we don’t?

Deep Uncertainty

What Will CO2 Emissions Be In 2100?

How high do you think CO2 emissions be in 2100?

How High Will CO2 Emissions Be In 2100?

Text: VSRIKRISH to 22333

Why Can’t We Agree?

Future CO2 emissions are dependent on multiple factors which are difficult to forecast:

- economic output

- technological change

- policies and governance

Deep Uncertainty

When there is no consensus probability for an uncertainty, we refer to it as a deep uncertainty.

Another Relevant Quote!

Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns — the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tends to be the difficult ones.

– Donald Rumsfeld, 2002 (emphasis mine)

Translating the Word Salad

- Known Knowns: Certainty

- Known Unknowns: “Shallow” Uncertainty

- Unknown Unknowns: “Deep” Uncertainty or ambiguity

Impacts of Deep Uncertainty

- Are you sure about the parameter values you’ve chosen?

- Are you sure about the probabilities you’ve assigned to Monte Carlo inputs or scenarios?

We can test the extent to which these different assumptions matter using sensitivity analyses.

Sensitivity Analysis

Factor Prioritization

Many parts of a systems-analysis workflow involve potentially large numbers of modeling assumptions, or factors:

- Model parameters/structures

- Forcing scenarios/distributions

- Tuning parameters (e.g. for simulation-optimization)

Additional factors increase computational expense and analytic complexity.

Prioritizing Factors Of Interest

- How do we know which factors are most relevant to a particular analysis?

- What modeling assumptions were most responsible for output uncertainty?

Source: Saltelli et al (2019)

Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis is…

the study of how uncertainty in the output of a model (numerical or otherwise) can be apportioned to different sources of uncertainty in the model input

— Saltelli et al (2004), Sensitivity Analysis in Practice

Why Perform Sensitivity Analysis?

Source: Reed et al (2022)

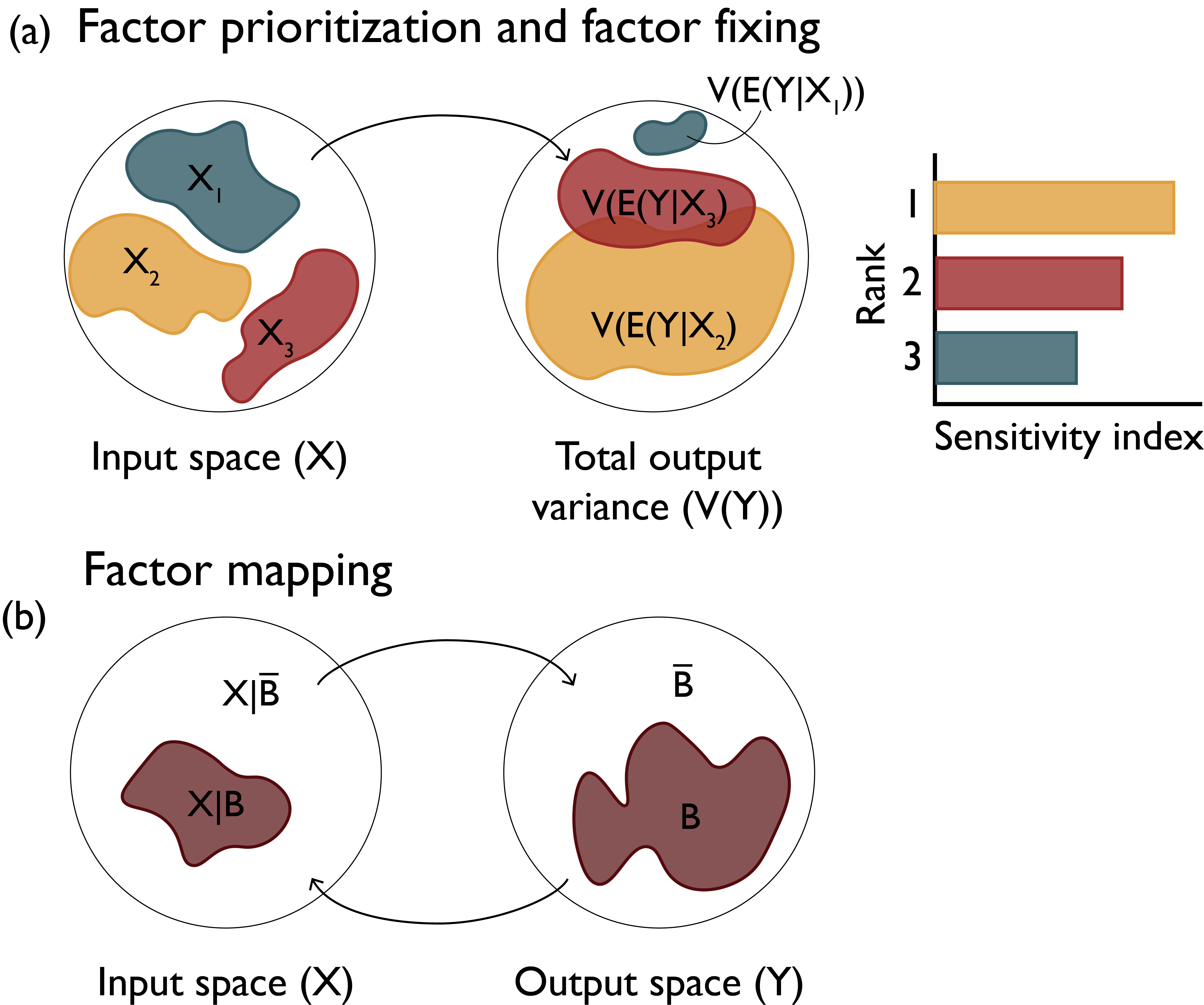

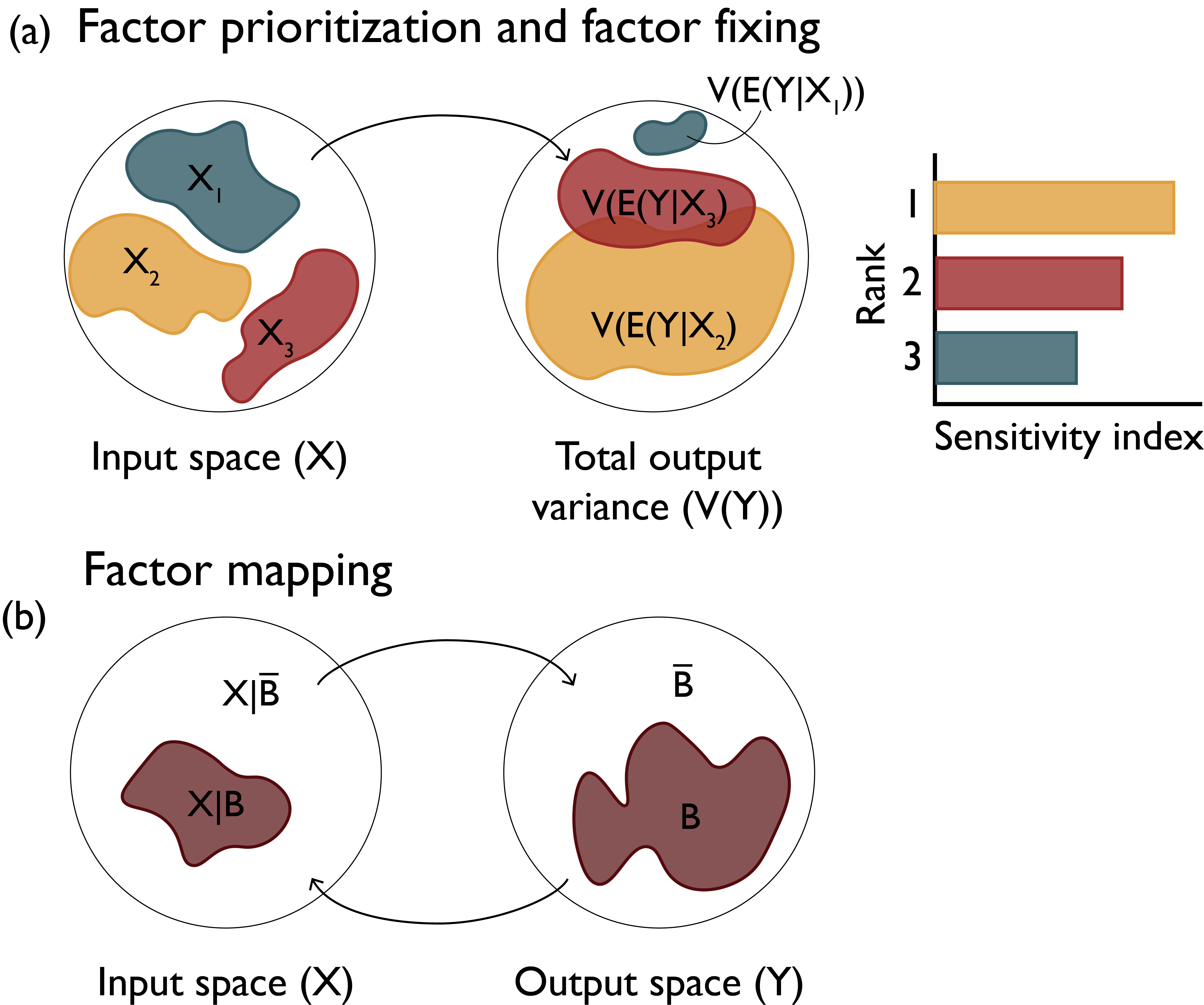

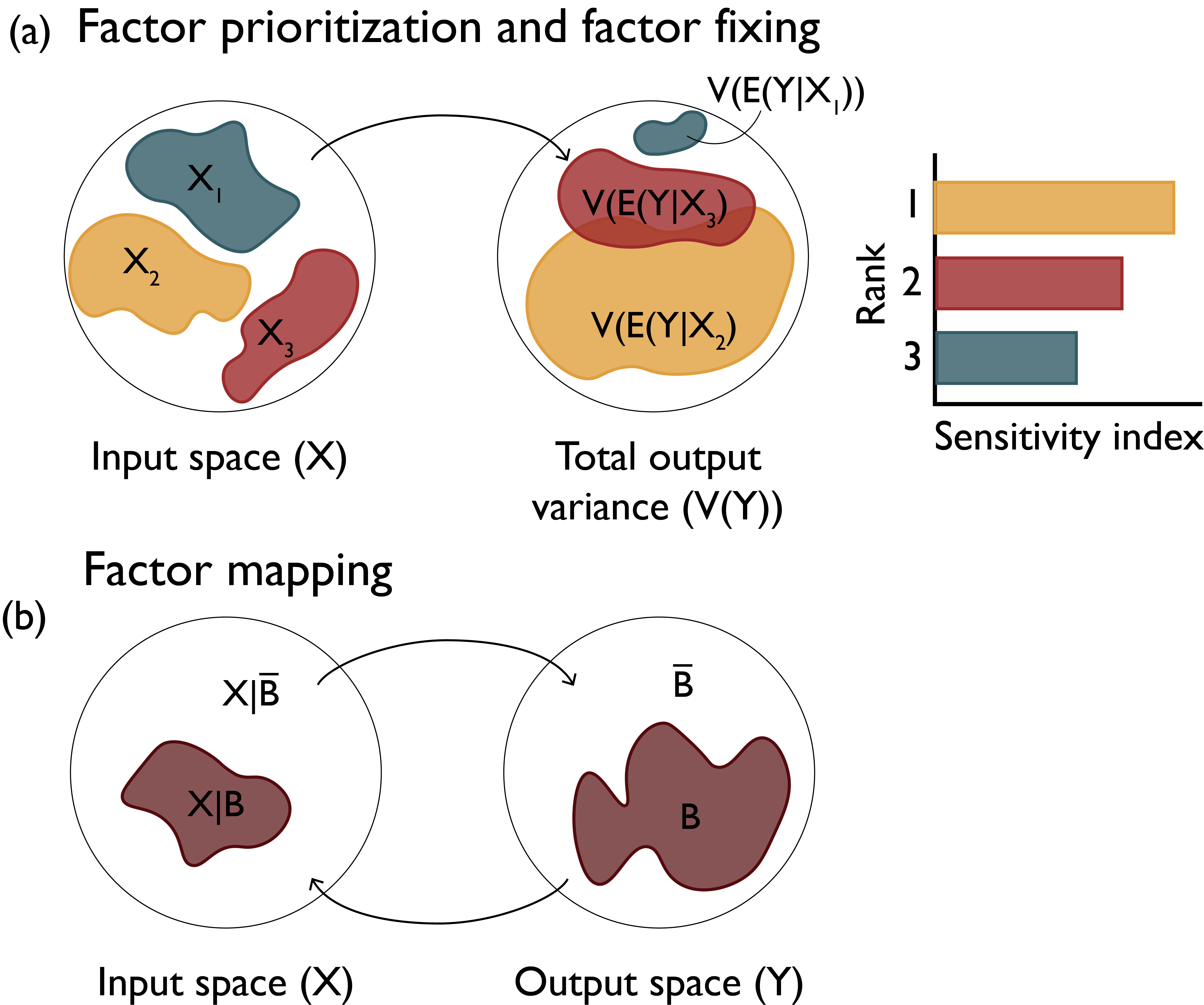

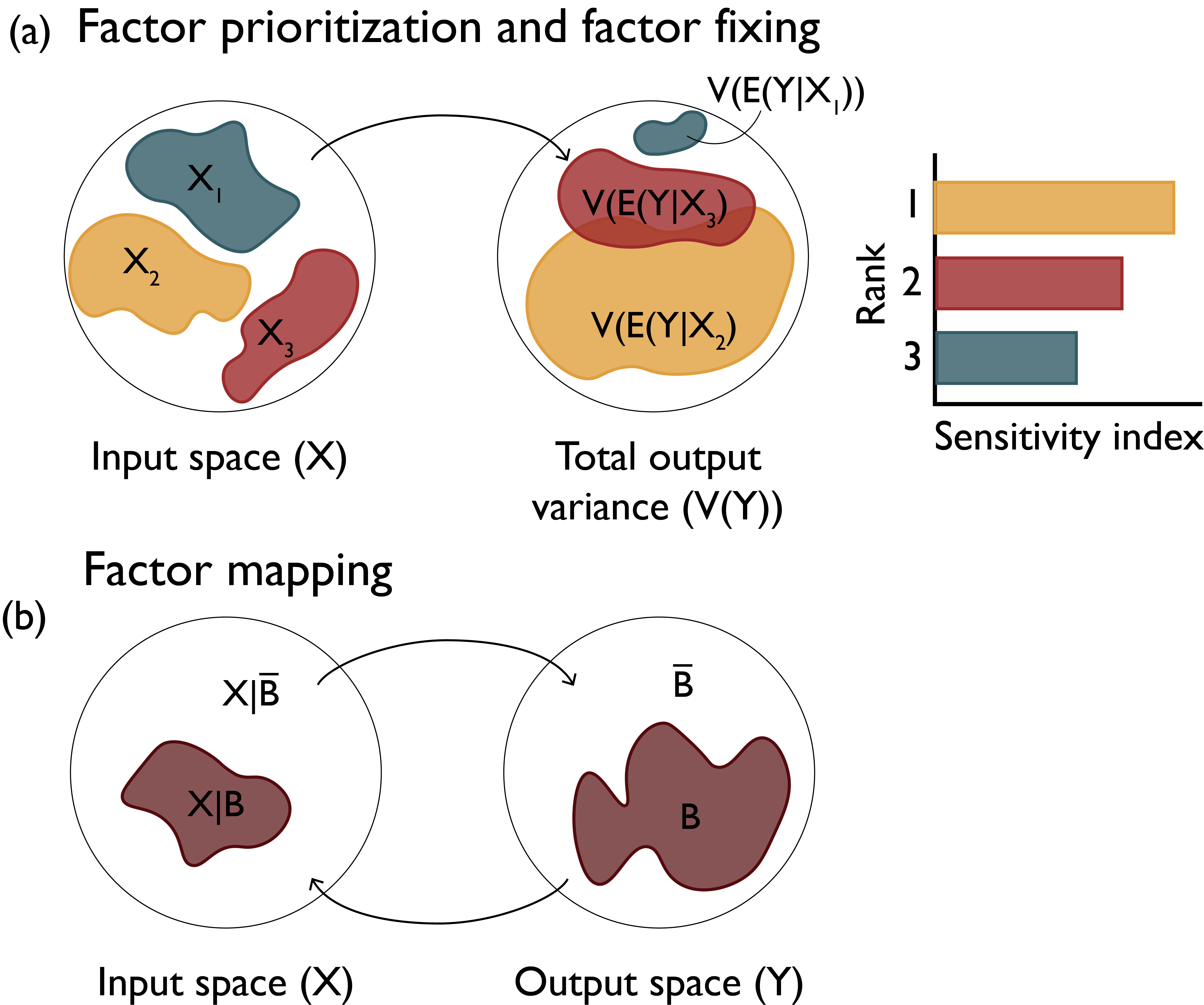

Factor Prioritization

Which factors have the greatest impact on output variability?

Source: Reed et al (2022)

Factor Fixing

Which factors have negligible impact and can be fixed in subsequent analyses?

Source: Reed et al (2022)

Factor Mapping

Which values of factors lead to model outputs in a certain output range?

Source: Reed et al (2022)

Example: Shadow Prices Are Sensitivities!

We’ve seen one example of a quantified sensitivity before: the shadow price of an LP constraint.

The shadow price expresses the objective’s sensitivity to a unit relaxation of the constraint.

Shadow Prices As Sensitivities

Code

x1 = 0:1200

x2 = 0:1400

f1(x) = (600 .- 0.9 .* x) ./ 0.5

f2(x) = 1000 .- x

f3(x) = (650 .- 0.9 .* x) ./ 0.5

p = plot(0:667, min.(f1(0:667), f2(0:667)), fillrange=0, color=:lightblue, grid=true, label="Feasible Region", xlabel=L"x_1", ylabel=L"x_2", xlims=(-50, 1200), ylims=(-50, 1400), framestyle=:origin, minorticks=4, right_margin=4mm, left_margin=4mm, legendfontsize=14, tickfontsize=16, guidefontsize=16)

plot!(0:667, f1.(0:667), color=:brown, linewidth=3, label=false)

plot!(0:1000, f2.(0:1000), color=:red, linewidth=3, label=false)

annotate!(400, 1100, text(L"0.9x_1 + 0.5x_2 = 600", color=:purple, pointsize=18))

annotate!(1000, 300, text(L"x_1 + x_2 = 1000", color=:red, pointsize=18))

plot!(size=(1200, 600))

Z(x1,x2) = 230 * x1 + 120 * x2

contour!(0:660,0:1000,(x1,x2)->Z(x1,x2), levels=5, c=:devon, linewidth=2, colorbar = false, clabels = true)

scatter!(p, [0, 0, 667, 250], [0, 1000, 0, 750], markersize=10, z=2, label="Corner Point", markercolor=:orange)

plot!(0:667, f3.(0:667), color=:brown, linewidth=3, label=false, linestyle=:dash)Shadow Prices As Sensitivities

Sorting by Shadow Price ⇄ Factor Prioritization

Keeping Constraints With Low Shadow Prices Fixed ⇄ Factor Fixing

Types of Sensitivity Analysis

Categories of Sensitivity Analysis

- One-at-a-Time vs. All-At-A-Time Sampling

- Local vs. Global

One-At-A-Time SA

Assumption: Factors are linearly independent (no interactions).

Benefits: Easy to implement and interpret.

Limits: Ignores potential interactions.

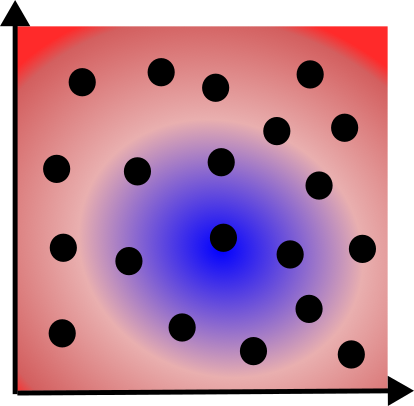

All-At-A-Time SA

Number of different sampling strategies: full factorial, Latin hypercubes, more.

Benefits: Can capture interactions between factors.

Challenges: Can be computationally expensive, does not reveal where key sensitivities occur.

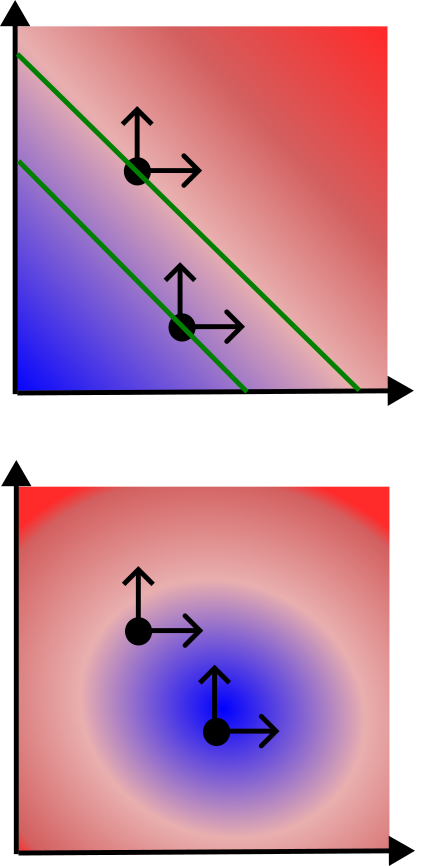

Local SA

Local sensitivities: Pointwise perturbations from some baseline point.

Challenge: Which point to use?

Global SA

Global sensitivities: Sample throughout the space.

Challenge: How to measure global sensitivity to a particular output?

Advantage: Can estimate interactions between parameters

Parameter Interactions

Source: SciPy Documentation

How To Calculate Sensitivities?

Number of approaches. Some examples:

- Derivative-based or Elementary Effect (Method of Morris)

- Regression

- Variance Decomposition or ANOVA (Sobol Method)

- Density-based (\(\delta\) Moment-Independent Method)

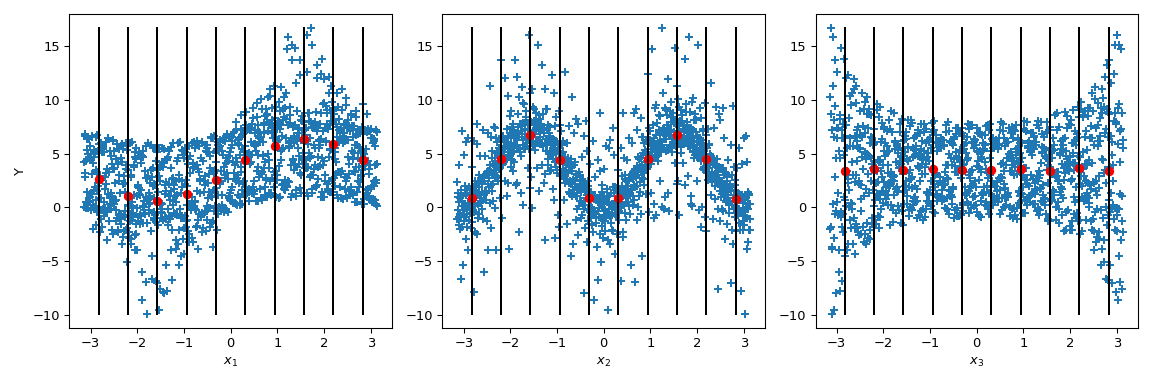

Example: Lake Problem

Parameter Ranges

For a fixed release strategy, look at how different parameters influence reliability.

Take \(a_t=0.03\), and look at the following parameters within ranges:

| Parameter | Range |

|---|---|

| \(q\) | \((2, 3)\) |

| \(b\) | \((0.3, 0.5)\) |

| \(ymean\) | \((\log(0.01), \log(0.07))\) |

| \(ystd\) | \((0.01, 0.25)\) |

Method of Morris

The Method of Morris is an elementary effects method.

This is a global, one-at-a-time method which averages effects of perturbations at different values \(\bar{x}_i\):

\[S_i = \frac{1}{r} \sum_{j=1}^r \frac{f(\bar{x}^j_1, \ldots, \bar{x}^j_i + \Delta_i, \bar{x}^j_n) - f(\bar{x}^j_1, \ldots, \bar{x}^j_i, \ldots, \bar{x}^j_n)}{\Delta_i}\]

where \(\Delta_i\) is the step size.

Method of Morris

Code

function lake(a, y, q, b, T)

X = zeros(T+1, size(y, 2))

# calculate states

for t = 1:T

X[t+1, :] = X[t, :] .+ a[t] .+ y[t, :] .+ (X[t, :].^q./(1 .+ X[t, :].^q)) .- b.*X[t, :]

end

return X

end

function lake_sens(params)

Random.seed!(1)

T = 100

nsamp = 1000

q = params[1]

b = params[2]

ymean = params[3]

ystd = params[4]

lnorm = LogNormal(ymean, ystd)

y = rand(lnorm, (T, nsamp))

crit(x) = (x^q/(1+x^q)) - b*x

Xcrit = find_zero(crit, 0.5)

X = lake(0.03ones(T), y, q, b, T)

rel = sum(X[T+1, :] .<= Xcrit) / nsamp

return rel

end

Random.seed!(1)

s = gsa(lake_sens, Morris(),

[(2, 3), (0.3, 0.5), (log(0.01), log(0.07)),

(0.01, 0.25)])

p1 = bar([L"$q$", L"$b$", "ymean", "ystd"], (abs.(s.means) .+ 0.01)', legend=false, title="Sensitivity Index Means")

p2 = bar([L"$q$", L"$b$", "ymean", "ystd"], (s.variances .+ 0.01)', legend=false, yaxis=:log, title="Sensitivity Index Variances")

plot(p1, p2, layout=(2,1), size=(1200, 600))Sobol’ Method

The Sobol method is a variance decomposition method, which attributes the variance of the output into contributions from individual parameters or interactions between parameters.

\[S_i^1 = \frac{Var_{x_i}\left[E_{x_{\sim i}}(x_i)\right]}{Var(y)}\]

\[S_{i,j}^2 = \frac{Var_{x_{i,j}}\left[E_{x_{\sim i,j}}(x_i, x_j)\right]}{Var(y)}\]

Sobol’ Method: First and Total Order

Code

samples = 1_000

sampler = SobolSample()

lb = [2, 0.3, log(0.01), 0.01]

ub = [3, 0.5, log(0.07), 0.25]

A, B = QuasiMonteCarlo.generate_design_matrices(samples, lb, ub, sampler)

s = gsa(lake_sens, Sobol(order=[0, 1, 2], nboot=10), A, B)

p1 = bar([L"$q$", L"$b$", "ymean", "ystd"], (abs.(s.S1) .+ 0.01), legend=false, title="First-Order Sensitivity Index")

p2 = bar([L"$q$", L"$b$", "ymean", "ystd"], (s.ST .+ 0.01), legend=false, yaxis=:log, title="Sensitivity Index Variances", ylimits=(0, 1))

plot(p1, p2, layout=(2,1), size=(1200, 600))Sobol’ Method: Second Order

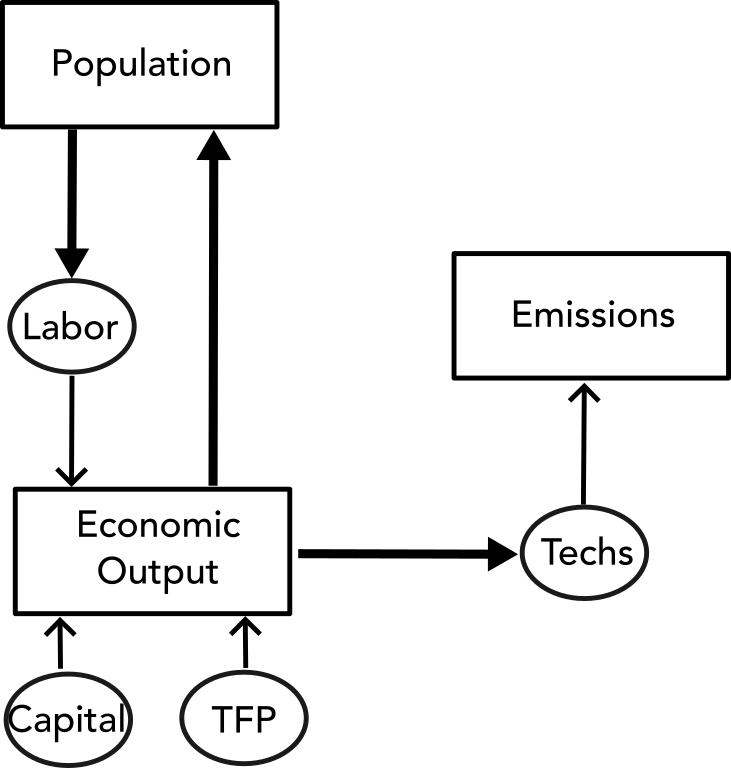

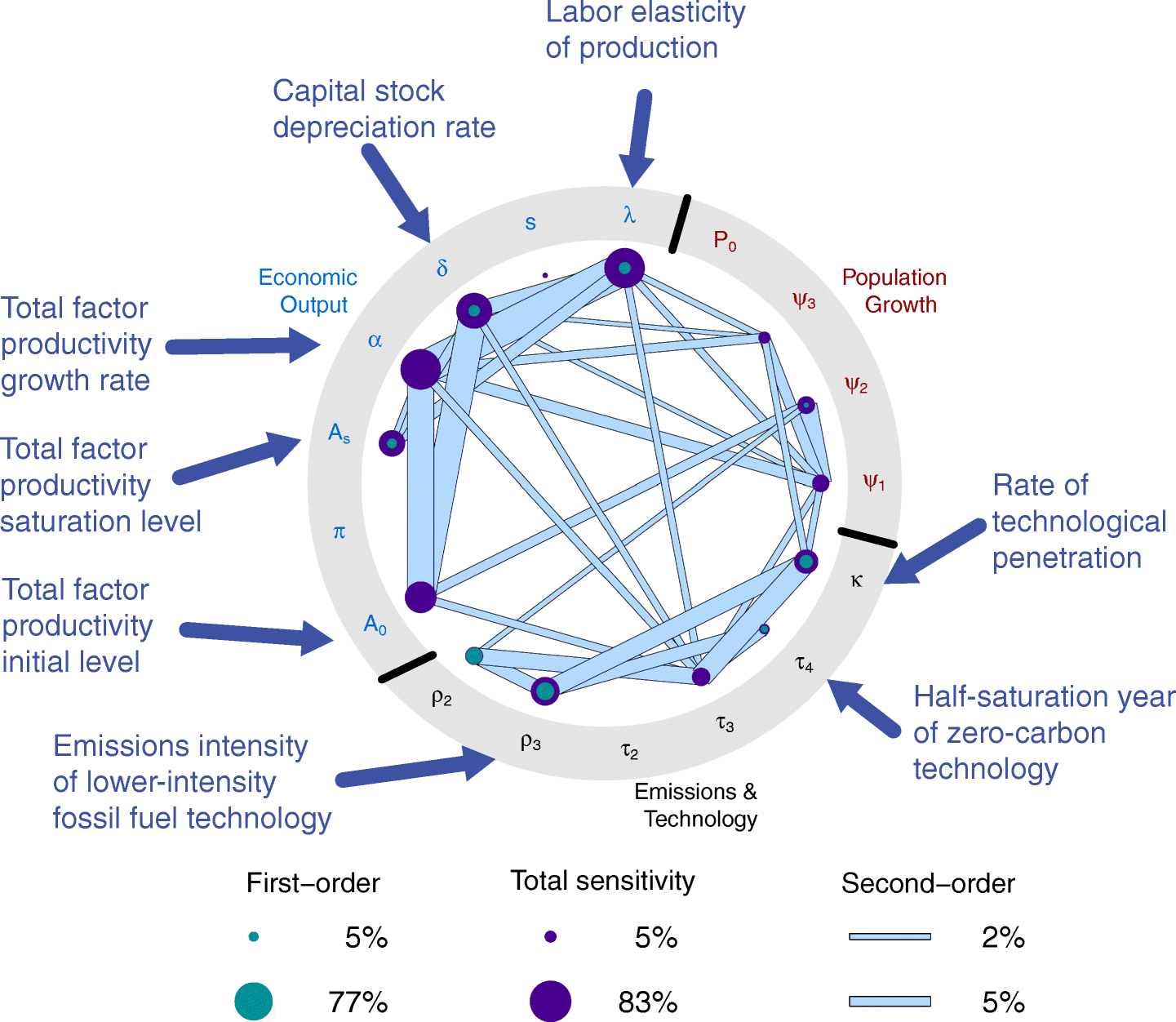

Example: Cumulative CO2 Emissions

Think about the joint population-economic-emissions system:

Example: Cumulative CO2 Emissions

Source: Srikrishnan et al (2022)

Key Takeaways

Key Takeaways (Sensitivity Analysis)

- Sensitivity Analysis involves attributing variability in outputs to input factors.

- Factor prioritization, factor fixing, factor mapping are key modes.

- Different types of sensitivity analysis: choose carefully based on goals, computational expense, input-output assumptions.

- Design of experiments (sampling strategy) can be very important: pay attention to details of method!

- Many resources for more details.

Upcoming Schedule

Happy Thanksgiving!

After Break: Simulation-Optimization, no class on 12/8

Assessments

HW5: Due 12/4

Projects: Take stock if you’re on track; please reach out if not!